This post discusses the civil liberties implications of the coronavirus quarantines taking place in 2020 in Canada. There are federal quarantine laws and provincial quarantine laws, which obviously vary from province to province. The federal and most provincial quarantine laws were updated after the 2003 SARS crisis, during which time all Canadian governments of all levels discovered that they did not have the legal tools to do what public health officials recommended. It was as chaotic then in Canada as COVID19 seems to be in the US, Italy, and other nations unprepared for COVID19.

The new emergency management laws passed post-SARS have not been tested legally, in terms of litigation regarding quarantine laws. In other words, the contemporary use of quarantine laws feels like uncharted legal territory.

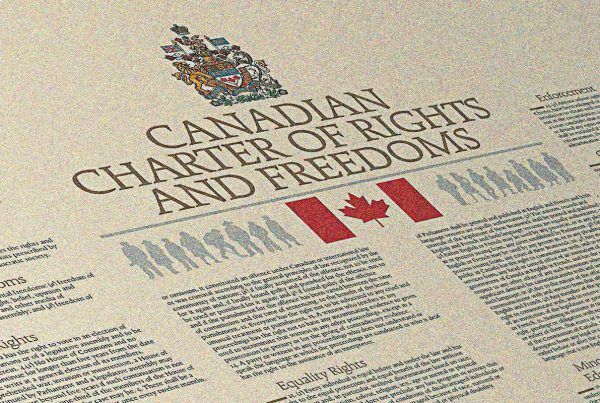

CCLA’s view is that the Charter of Rights and Freedoms requires the government to quarantine only where explicitly prescribed by statute, which ought to be narrowly construed, although less strictly construed in circumstances attaching to criminal law detention. Furthermore, public officials must ensure that the quarantined have adequate living conditions and the effective right to counsel. Otherwise, the federal legislation, at least, appears constitutional on its face. The risks arise with respect to the particular conditions of the quarantined, and any hint of racial profiling taking place. Within the little case law on point, the courts tend to defer to public health policy objectives. However, more expanded forms of quarantine such as city-wide lockdowns or quarantines that target a stigmatized or racialized community (today, people of Asian descent; tomorrow, maybe people of national descent where COVID19 outbreaks take place) would be vulnerable to a constitutional challenge.

BACKGROUND FACTS

In late December 2019, health officials in Wuhan, China, detected the outbreak of a new virus known eventually called COVID19. On January 23, 2020, the Chinese government imposed a complete lockdown on the city of Wuhan.

About 370 Canadians in Wuhan requested evacuation to Canada. The Canadian government responded by chartering two planes and securing seats on a U.S. government flight. The returnees were quarantined in a hotel in Canadian Forces Base (CFB) Trenton, a military base approximately 170 kilometres east of Toronto. Those Canadians were released after the expiration of their 14-day quarantine; none tested positive for the coronavirus. Recently, Canadians were evacuated from a California-docked cruise ship to be transported to and quarantined at the same military base.

LEGAL FRAMEWORK IN ONTARIO AND CANADA

Regarding the CFB Trenton (Ontario) quarantines, the federal Quarantine Act empowers Canada to control the international movement of people and goods in the event of a health emergency, while the provincial Health Protection and Promotion Act empowers Ontario to impose quarantines within the province. Thus, the federal act was applied to the CFB Trenton quarantine because the government was dealing with returnees from China. By contrast, the provincial act was used during the 2003 SARS crisis to quarantine persons who were already in Ontario. While other types of legislation may also be relevant to pandemics, such as Ontario’s Emergency Management Act or the Constitution’s peace, order, and good government power, this section focuses on the Quarantine Act and Health Protection and Promotion Act.

THE FEDERAL QUARANTINE ACT

The Quarantine Act grants the government broad powers to control international travel of persons and goods in times of disease. The quarantine at CFB Trenton was authorised under an emergency order made under s. 58(1) of the Quarantine Act, which provides as follows:

Order prohibiting entry into Canada

58 (1) The Governor in Council may make an order prohibiting or subjecting to any condition the entry into Canada of any class of persons who have been in a foreign country or a specified part of a foreign country if the Governor in Council is of the opinion that

(a) there is an outbreak of a communicable disease in the foreign country;

(b) the introduction or spread of the disease would pose an imminent and severe risk to public health in Canada;

(c) the entry of members of that class of persons into Canada may introduce or contribute to the spread of the communicable disease in Canada; and

(d) no reasonable alternatives to prevent the introduction or spread of the disease are available.

This power was previously used during the 2014 Ebola outbreak to impose reporting and screening obligations on persons who had come from Guinea within a 21-day period. Since there is no statutory appeal from s. 58(1), the Charter’s s. 10(c) habeas corpus remedy would be the best way to challenge an order under that section. s. 7 of the Quarantine Act also empowers the government to designate any location as a quarantine facility – in this case, CFB Trenton.

The Quarantine Act also authorises non-quarantine disease control measures. For example, s. 28 of the legislation enables the appointment of specialised officers who can detain and medically examine any international traveller if they suspect them to be a public health risk or if they refuse to submit to medical examination. Unlike s. 58(1), there is a statutory appeal (s. 29[6]) from this type of detention that must be heard by the reviewing officer “within 48 hours after receiving the request [for review of detention]”. S. 39(1) empowers officers to stop, search, divert, or destroy any “conveyance” (e.g. an aircraft or shipping container) that is entering or departing Canada if they feel that the conveyance is harbouring a communicable disease. These powers were used during the 2003 SARS outbreak to detain and decontaminate an aircraft at Vancouver International Airport because a passenger had SARS-like symptoms.

THE ONTARIO QUARANTINE LAW

While only federal legislation has been used in the crisis thus far, provincial legislation could be activated if the virus continues to spread in Ontario. The provincial Health Protection and Promotion Act pertains to public health in Ontario generally; Parts VI and V of the Act pertain to communicable disease and quarantine. S. 22(2) of the Act empowers public health officers appointed under the statute to issue quarantine orders if they are necessary to prevent a communicable disease. These quarantine orders take many forms, including requiring a person or class of persons to isolate themselves, seek treatment, or close premises. There is a statutory appeal for these quarantine orders, but that appeal process may be illusory; unlike the federal statute’s 48-hour limit, s. 44(5) of the provincial statute only requires that a hearing be held “within fifteen days after receipt by the Board of the notice in writing requiring the hearing”, by which time the order may have already expired because most quarantine orders are measured in terms of weeks.

The 2003 SARS crisis provides an example of how the Health Protection and Promotion Act was used. SARS emerged in China in November 2002 and spread to Canada through a traveller; the disease then spread throughout hospitals in Toronto to infect a total of 438 persons. Ontario public health officials asked over 13,000 Toronto residents to voluntarily observe quarantine, most of whom did; mandatory orders were resorted to in 27 cases.

CIVIL LIBERTIES ISSUES

A quarantine is prima facie a form of detention that engages various Charter rights such as liberty (s. 7) or freedom from arbitrary detention (s. 9, 10). On the one hand, a detention is a detention, with varying degrees of limitations on a person’s liberty and security of the person, and varying degrees of due process applying to the liberty infringement. To lose one’s freedom of movement and residence and interaction with others, to be constricted to a particular property, even if quarantined at home, is a version of house arrest or institutional custody. Depending on the conditions, this amounts to one of the most serious lawful infringements of our fundamental freedoms in Canada. This is the state telling people that they are not free to go; they are not free to interact with their family and friends; they cannot hug their kids or vice versa; they are not free as they were prior to the imposition of a quarantine.

On the other hand, that liberty infringement in a quarantine context may be different from other contexts, such as detention pursuant to the Criminal Code, provincial offences acts, or the common law. In the criminal and quasi-criminal context, the prejudice is unquestionably greater than in the public health quarantine context. While there is a stigma attaching to the quarantined, it is less than that of a pre-trial detention in a correctional facility, let alone a custodial sentence in a provincial or federal facility. Other than that stigma, there are also less adverse effects following a quarantine detention than a criminal law detention. There is no ‘quarantine record’ saved permanently or otherwise in police records. There may be adverse effects on employment and housing, but that would require the employer or landlord to be made aware of the quarantined, which would not arise from public records checks. Nor are there necessarily any conditions attaching to liberty post-quarantine, such as is the case with those paroled and on probation.

Nevertheless, the effect on one’s mental health during a quarantine should not be understated. This amounts to a violation of security of the person under section 7 of the Charter. This will, by necessity, vary from person to person, depending on their natural level of anxiety, depression or other conditions. Someone addicted to alcohol or cannabis, both legal products, will face particular challenges during quarantine. To imagine that there are no addicts or alcoholics or mentally ill among the hundreds quarantined at CFB Trenton is statistically naïve.

Accordingly, in order for CCLA to continue to adequately honour and support our legal fights for the rights of defendants, prisoners, those in solitary confinement, and convicts with a criminal record, CCLA ought to consider that a quarantine is no federal solitary confinement, except of course when it is, but that goes to the quarantine conditions. From a principled perspective, then, the impact on the liberty and security of the person of the quarantined may be less onerous than criminal and quasi-criminal law detentions. It follows that the due process attaching to a quarantine may not be less than that in the penal context.

Quarantine is legally not a punishment and therefore attracts less due process rights than detentions that are punishments. On the other hand, the quarantined are unquestionably also innocent, so a quarantine no doubt may feel like a punishment to some. That is the infringement of liberty, which does indeed attract a level of due process and proportion consistent with its purpose. Just how long one may be held must be prescribed by statute or regulation. The conditions must be better than prison but less than a spa. And there ought to be rights of appeal. This would apply primarily to circumstances where someone believes themselves to have been mistakenly quarantined, or where the quarantine was no public health official’s error, but was applied in an overbroad fashion, akin to what is happening in Italy in March 2020.

There is little case law on Charter challenges to quarantine orders, although three cases suggest that there would be judicial deference to a public health order. For example, in Toronto (City, Medical Officer of Health) v. Deakin [2002] O.J. No. 2777 (Ct. J.), the Ontario Court of Justice upheld a four-month extension on a four-month detention of a potentially infectious tuberculosis patient. The court held that his s. 7 liberty rights were violated but the violation was justified under s. 1:

What was done to [the patient] was carried out for the protection of public health and the prevention of the spread of tuberculosis, a disease that [a medical specialist] described as extremely contagious. [26]

In a second case, Re George Bowack, [1892] 2 B.C.R. 216 (S.C.), this time pre-Charter, the British Columbia Supreme Court sided with public health imperatives. In that 1892 case, a traveler with smallpox was detained in a hospital under a municipal bylaw that was passed pursuant to provincial legislation. The court upheld the legislation as legitimate and rejected the traveler’s writ of habeas corpus.

In a third case, Canadian AIDS Society v Ontario (1995) 25 O.R. (3d) 388 (Gen. Div.), an Ontario superior court adjudicated the constitutionality of HIV reporting requirements under various provincial healthcare acts. These reporting requirements operated to compel the Canadian Red Cross Society to inform public health authorities that the Red Cross possessed donated blood samples that were HIV positive. The court weighed the privacy interest of the blood donors against public health considerations and upheld the reporting requirements because “the state objective of promoting public health for the safety of all will be given great weight. [133]” There appear to be no cases where a public health-related detention has been successfully challenged.

Furthermore, the CFB Trenton quarantine is relatively measured; it lasts for 14 days (the current maximum symptomatic period for the coronavirus) and is constrained to people who have come from Wuhan, the epicenter of the disease outbreak, and those who had been quarantined on a cruise ship eventually landing in California.

More draconian quarantine measures have been applied in other liberal democracies such as the U.S., where quarantine has been applied to all American returnees who have visited the whole of Hubei province (where Wuhan city is located), and where a travel ban was placed upon Europeans entering the US, or in New Zealand, where any New Zealander returning from anywhere in China must be quarantined, or in Italy, where a nation-wide quarantine was issued by decree.

While there is debate over the efficacy of quarantines, there is at least some degree of support for their use in Canada to date, which suggests that the CFB Trenton quarantine is within the range of legitimate public health policy choices.

QUARANTINE CONDITIONS AND ACCESS TO JUSTICE

CCLA will advocate for legal reform going forward. The government ought to bake minimum standards for living conditions into the federal and provincial legislation. At present, those standards of relative comfort ought to be the minimum to which the government is held. Given that Health Minister Patty Hadju has acknowledged that a 14-day quarantine will be “very stressful”, poor quarantine conditions could constitute a form of state-imposed psychological stress that would violate security of the person under s. 7 of the Charter. Especially dire quarantine conditions could even be a form of cruel and unusual treatment under s. 12 of the Charter, which requires state treatment “to be so excessive as to outrage standards of decency” (see, for e.g., R. v. Ferguson, 2008 SCC 6 at para. 14). This is a high standard that might only be met if the quarantined were deprived of adequate food, housed in dirty conditions, continuously confined in rooms without meaningful access to the outdoors, or a combination of these or other hardship conditions. In the case of CFB Trenton, however, the hotel appears to be sufficiently comfortable – families are staying together in ensuite rooms that have high-speed internet and food delivery.

However, there is no guarantee that future quarantines will have these appropriate comforts because the federal and provincial legislation are silent on quarantine conditions. S. 62(c)-(c.1) of the federal legislation does empower the Governor-in-Council to make regulations regarding different aspects of quarantine facilities, but none appear to have been promulgated. Thus, CCLA will argue for statutes or regulations that prescribe minimum living standards for quarantines.

CCLA has already advocated for the federal government to respect, deliver and coordinate the right of the quarantined to have effective access to counsel (s. 11 Charter), pursuant to a recent public letter to Hon. David Lametti, the Attorney-General of Canada.

It is important to note that s. 11 Charter jurisprudence suggests that what the Charter requires is limited to the government informing the quarantined of their rights to counsel and the contact information for legal aid for those eligible for it (see R v Bartle [1994] 3 S.C.R 173), in addition to facilitating their access to a telephone if needed (see R v Manninen [1987] 1 S.C.R. 1233, 1241). Of course, it remains open to CCLA to advocate over and beyond the bare minimum, and it would certainly be welcomed if the federal authorities did facilitate legal services for all of the quarantined. To date, the Attorney General has taken the position that allowing access to self-help measures is enough. Given that few can find or afford counsel, this is not good news for Canadian civil liberties.

MORE EXTREME EMERGENCY MEASURES

A city-wide lockdown similar to the one imposed on Wuhan by the Chinese government would almost certainly be unconstitutional, as legal experts have pointed out. However, measures less extreme than a city-wide lockdown could still be unconstitutional if they were overbroad or grossly disproportionate; for example, the quarantine of persons who are at low risk of infection or of entire city blocks because of a few residents suspected of infection.

CCLA’s position is therefore that any expansion of the quarantine regime must be clearly justified by empirically sound, scientific evidence and should not be more liberty-restrictive than necessary. That said, while s. 22(7) of the provincial legislation requires public health officials to justify in writing their decision to quarantine, the only way the statute enables testing of whether those reasons are backed up by evidence is through the statutory appeal process, which may be moot (as pointed out above) because a hearing need only be conducted after 15 days.

Also, no judicial authority is needed to quarantine, unlike, say, pre-trial detention without bail. While we are unaware of any political influence bearing upon public health officials federally in this case, nor is there any process prescribed, contrary to administration law principles.

Another potential issue is equality-related – if the government were to enact detention measures that disproportionately and unjustifiably affected a particular racialized community, such as the Chinese-Canadian community, e.g., quarantine of a city’s Chinatown. That would raise an s. 7 or 15 Charter equality issue, as well as engaging federal and provincial human rights commissions. Prejudices have historically informed public health policy globally and in North America; for example, in 1900, U.S. President McKinley ordered a quarantine of all Chinese and Japanese residents in part because “Asians were particularly susceptible to plague because of their dietary reliance on rice rather than animal protein.” Of course, there is no evidence of Canadian authorities repeating such naked racism today, but CCLA will always take the opportunity to express solidarity with an embattled community that is currently sounding the alarm over coronavirus-induced racism.

About the Canadian Civil Liberties Association

The CCLA is an independent, non-profit organization with supporters from across the country. Founded in 1964, the CCLA is a national human rights organization committed to defending the rights, dignity, safety, and freedoms of all people in Canada.

For the Media

For further comments, please contact us at media@ccla.org.