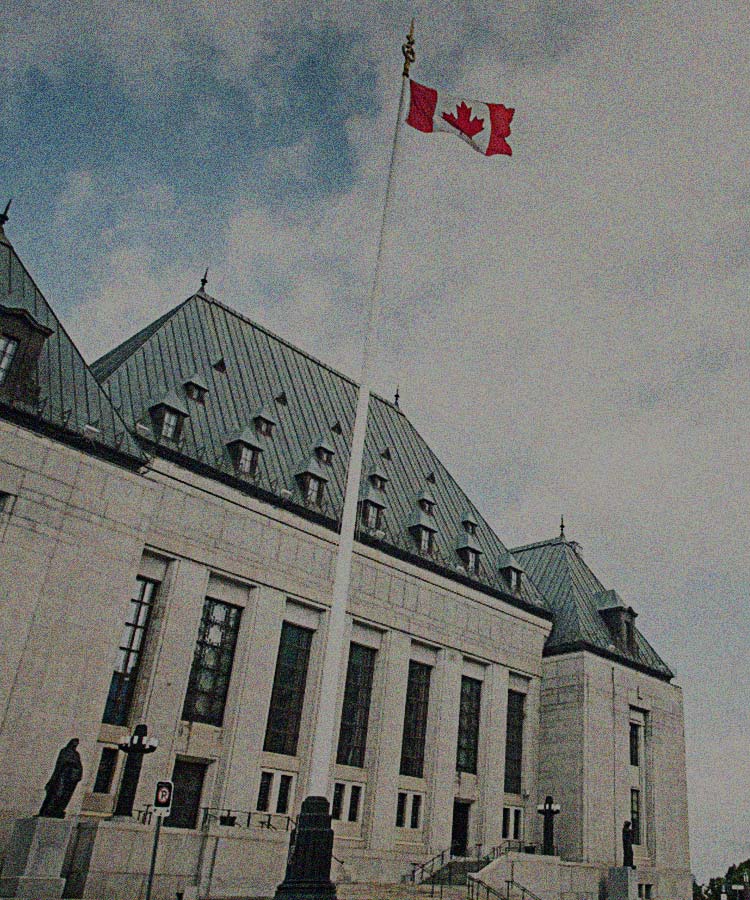

It’s a loss for privacy in a disappointing Supreme Court decision released April 18 in R v Mills. The Court issued four different reasons in this decision, a reflection of the complicated issues at stake in a case that combines a police sting operation, private messaging between an officer posing as a young girl and the accused over an online platform, and the use of screen capture technology to record ongoing electronic conversations, all without judicial warrant.

CCLA intervened in this case to argue that a zone of privacy for electronic conversations is essential in a free and democratic society. People in Canada should be able to conduct private one-on-one conversations, free of state interference. We also sought confirmation from the Court that the finding in R v Marakah that text messages may carry reasonable expectations of privacy also carries over to other forms of electronic conversations, such as the ubiquitous messenger applications that many of us use as an alternative to texting.

On that point, the Court agreed, with the plurality writing that the one-on-one electronic conversations in this case “have no legally significant distinction from text messages.” This confirmation of a technologically neutral approach, that focuses on the private nature of the conversations rather than the platform on which they occur, is a small battle won.

But Justices Abella, Gascon and Brown go on to conclude that the accused’s expectations of privacy in this case were not objectively reasonable, because “adults cannot reasonably expect privacy online with children they do not know.” While s. 8 Charter protection is generally content neutral, the fact that the relationship was engineered by police, and the socially abhorrent nature of child luring, weighed more heavily in the reasons written by Brown J.: “This appeal involves a particular set of circumstances, where the nature of the relationship and the nature of the investigative technique are decisive.”

Justices Wagner and Karakatsanis presented different reasons for finding no s. 8 breach occurred. They found that when undercover officers are communicating in writing with individuals, there is no search or seizure because the officer is the intended recipient of the messages. Similarly, in written communication, they found that the screen capture of the message did not require judicial authorization because the sender, by engaging in written conversation, must have understood the recipient would have the ability to keep a copy of that conversation.

Only Justice Martin advanced the position that the state surveillance of the private conversation was, in fact, a search that violated s. 8, absent judicial authorization, and further, that the screen capture software did, in fact, constitute an interception within the meaning of the Criminal Code.

The ultimate effect this decision has on police sting operations will be something to watch—will it be applied only to investigations involving sexual predators and children, or will police read it as mitigating the need for judicial authorization more broadly in online sting operations? Will police attempt to extend the reasoning to apply to surveillance of other vulnerable populations, such as racialized persons or groups? The reasons of Wagner C.J. and Karakatsanis J. did speak to narrow that possibility, noting that just because they found s. 8 was not engaged in this case “does not mean that undercover online police operations will never intrude on a reasonable expectation of privacy.”

Section 8 Charter protections require a balance between the public’s interest in being left alone and the government’s interest in law enforcement. But that balancing should occur after, not within, the reasonable expectation of privacy analysis. Justice Martin’s reasons lead ultimately to the same decision as the rest of the bench, with a very different analysis. She states the question to be answered cannot focus solely on adults who communicate online with children for an evil purpose, but must recognize the broader implications (that CCLA similarly identified) that are core to the case, namely, do “members of society have a reasonable expectation that their private, electronic communications will not be acquired by the state at its sole discretion”?

CCLA will continue to advocate for the latter.

We are grateful to our pro bono counsel Frank Addario and James Foy of Addario Law Group LLP for their work on this case.

About the Canadian Civil Liberties Association

The CCLA is an independent, non-profit organization with supporters from across the country. Founded in 1964, the CCLA is a national human rights organization committed to defending the rights, dignity, safety, and freedoms of all people in Canada.

For the Media

For further comments, please contact us at media@ccla.org.